The Secret of Japan’s Carpenters: How ‘Miyadaiku’ Techniques Construct Timeless Temples Without Nails

- Written by: LIVE JAPAN Editor

Wood construction has long thrived in Japan, where forests blanket about two-thirds of the country. Carpenters, working tirelessly to hone their craft, aim to create structures that can endure natural disasters and changing climates.

A crucial part of this history is the “miyadaiku,” or shrine carpenters, known for building shrines and temples. We spoke with representatives from Kongo-Gumi Co., Ltd in Osaka, the world's oldest company, founded in 578 A.D., to delve into the miyadaiku’s skilled techniques and the architectural excellence that Japan is proud of.

*This article includes advertising content.

Meet the Shrine Carpenters: Tracing the Journey of Miyadaiku

There are said to be more than 150,000 shrines and temples throughout Japan, all of which are built and repaired by miyadaiku.

More than 1,400 years ago, the organization of miyadaiku came into being in Japan. Shigemitsu Kongo, one of the shrine carpenters invited from Baekje by Prince Shotoku to build Shitennoji Temple, the first official Buddhist temple in Japan , founded the Kongo-Gumi.

Since then, the shrines and temples throughout Japan have been built by miyadaiku, ranging from repairing historical monuments of more than 1,000 years to planning and proposing the construction of new shrine pavilions.

Building Houses for the Divine - The Dawn of Miyadaiku

While some companies throughout Japan undertake the work of miyadaiku, Kongo-Gumi is home to one of Japan’s leading groups of miyadaiku carpenters, known as Takumikai, consisting of seven groups and approximately 100 members.

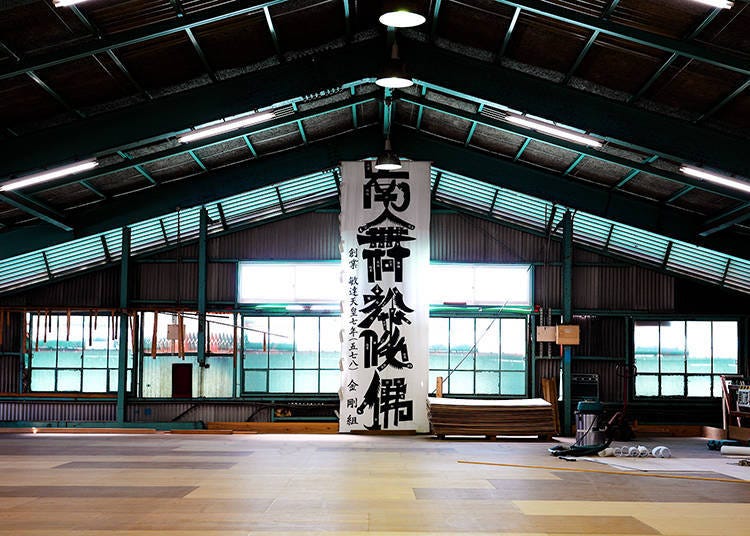

Upon visiting the Kansai Processing Center in Osaka Prefecture and touring the spacious, high-ceilinged facility, one can see the miyadaiku carpenters of each group working silently. Even though they are working on large-scale shrine buildings, very few machines are around.

“The architecture that miyadaiku works on are the objects of people’s faith, the ‘houses where the gods and buddhas dwell.’ That is why, in order to put our hearts and souls into each piece that goes into these constructions, we build them by hand with the utmost care,” says Kenichi Tone, Chairman of the Kongo Gumi. Not a single person in the workshop wastes time talking; they concentrate on the lumber in front of them, creating a constantly tense atmosphere.

The Art of Kigumi - How Shrine Carpenters Build Without a Single Nail

The most distinctive feature of miyadaiku is that the carpenters work the lumber by hand and are involved in every aspect of the construction process, including the finishing touches.

One of the most important techniques is “kigumi (wood joinery),” a traditional construction technique that connects pieces of wood without using any nails or metal fasteners. (Metal fasteners may be partially used as per regulations or as a secondary means of support.)

Japan’s climate is the primary reason for not using metal fasteners to connect joints. During summer in Japan, heavy rains and typhoons occur frequently, causing humidity and dampness to continue. Using nails, wedges, and other metal fasteners can inevitably rust from rain and humidity, causing the wood to rot and rendering it challenging to repair.

However, if a building is constructed entirely of lumber, it can absorb moisture when humidity is high and expel it when humidity is low, making the structure more durable than if metal fasteners are used.

Adapting to the climate, Japanese carpentry techniques have made great use of the characteristics of lumber, and house construction that coexists with wood has continued to be passed down through generations. (In general construction, metal fittings are used in various parts of the building because the service life of metal fittings is equivalent to or longer than the service life of the building.)

Miyadaiku Master 200+ Unique ‘Kigumi’ Woodworking Patterns in Their Craft

Wood joinery can be broadly classified into two types. The first is “tsugite (splicing joints),” which involves splicing two pieces of lumber to make a long post or beam. A grooved notch is carved out on the first end of the wood; on the second piece of wood, a tongue is cut out to fit the notch, like a puzzle.

The other type of wood joinery is the “shiguchi (connecting joints),” where two or more pieces of lumber are joined at a vertical intersection. As with the tsugite, the pieces of wood are shaved and fitted together.

The woodwork assembled by miyadaiku is so tightly fitted together that it remains stable even when external forces are applied. Still, the small gaps between the pieces of wood allow for force dispersion from earthquakes and typhoon vibrations.

Tsugite and shiguchi have long been handed down from master carpenters and builders, with over 200 types of joints in existence. Joints are used according to the wood’s shape and the structure’s finishing design.

“The buildings built by miyadaiku are different in the years leading up to 100 or 1,000 years. Not only the construction but also the restoration of the building after it has been built is thoughtfully considered. There are not many other professions in which one considers 1,000 years into the future, so to put it simply, miyadaiku are a group of eccentric people,” explains Shigeo Kiuchi , Takumikai master carpenter of Kiuchi Gumi. The persistence of these “eccentric group of people” serves as the foundation for building houses that will last for a thousand years to come.

Micrometre Precision - The First Step in Training to Be a Miyadaiku is Planing

The Kongo Gumi Takumi Nurturing School is located in the Kansai Processing Center. Here, young carpenters under the age of 20 who aspire to become miyadaiku are trained to carry on the traditional craftsmanship. These young carpenters enthusiastically engage in wood planing using a plane, a type of carpenter’s tool.

Wood planing not only smoothes the surface of lumber but also gives it a glossy sheen and water-repellent finish.

Planing, a common carpentry technique globally, usually involves pushing the plane. However, Japanese carpenters do it differently: they pull the plane. This method lets them shave wood into long, thin, almost transparent strips, some as fine as 30 microns – thinner than a hair. They start from the board’s edge, pulling the plane straight. After each pull, they check the smoothness by hand, continuing until it meets the master’s exacting standards.

Moisture Matters - How Carpenters Select and Manage Lumber

Careful selection and management of the lumber itself are also vital parts of the miyadaiku’s thorough attention to detail.

The process begins with a thorough quality check of the lumber once it has been delivered from the partner lumber supplier.

According to Mr. Kiuchi, “The carpenter’s ultimate task is to determine the dryness of the wood.” Freshly harvested lumber contains a high moisture content and is prone to splitting and warping when processed as it is.

Durable wood such as Hinoki, Sugi, and Kusunoki are used in Japanese wooden construction. These lumber types have long been associated with Japan, so much so that Nihon Shoki (The Chronicles of Japan), one of Japan’s oldest historical books published in 720, describes that “Sugi and Kusunoki should be used for boats, Hinoki for palaces, and Maki for coffins.”

The lumber used by the Kongo-Gumi is primarily Hinoki, which is found in Mount Yoshino in Nara Prefecture. The wood is generally straight and unyielding, and the core of the wood is rarely distorted. Only lumber that has passed inspections for grain (the pattern that appears on the surface of the wood), color, twists, and bends are used.

Finally, the workshop that Mr. Tone and Mr. Kiuchi showed was decorated with a banner that read “Namu Amidabutsu,” the Buddhist prayer of Amitabha. Upon closer look, the characters were formed using carpenter’s tools, such as chisels, hammers, and sickles.

This is the Banshoki Myogo, said to have been created by Prince Shotoku. “Cutting down a living tree is considered as ‘killing,’ thus symbolizing both the safety of the construction work and the Buddhist significance of the tools,” says Mr. Kiuchi.

Coexisting with wood since ancient times and building houses without ever neglecting the appreciation toward timber is one of the major characteristics of Japanese carpenters.

Resisting Rain and Humidity - The Secrets to Japanese Wooden Structures Lasting a Millennium

Many may wonder, “Why do wooden structures last so long in a country that is so hot, humid, and rainy like Japan?”

The reason why Japanese wooden structures continue to exist, even after being repaired over 100 or 1,000 years, reflects the ingenuity of Japanese carpenters who have worked diligently over many years to ensure that these structures can withstand humidity, rain, and wind and can undergo repeated restorations.

Wooden architecture isn’t just about stunning designs; it’s also great for insulation and controlling humidity. Plus, these buildings store carbon, helping in the fight against global warming. By combining carpenter smarts and skills with eco-friendly practices, Japan's wooden building techniques could really make a global impact.

- Area

- Category

*Prices and options mentioned are subject to change.

*Unless stated otherwise, all prices include tax.

Popular Tours & Activitiess

-

Ad

Discover Kyoto by the Sea: Explore Nature, History, and Culinary Tradition in "Another Kyoto"

-

Ad

From March 2026, Kyoto’s accommodation tax rate will change. What exactly is this tax used for?

-

Ad

Earthquake in Kyoto? Typhoon? What To Do If Disaster Strikes During Your Stay

-

Vintage Watch Hunting in Osaka (Umeda & Shinsaibashi): Rolex, Seiko, and Rare Finds

-

A First Look at NEMU RESORT’s 2026 Grand Renewal in Ise-Shima: A Resort Shaped by Village, Sea, and Forest

by: Guest Contributor

-

February Events in Kansai: Fun Festivals, Food, and Things to Do in Kyoto & Osaka

-

5 Best Hotels Near Universal Studios Japan (Osaka): Top-Rated Places to Stay

by: WESTPLAN

-

Sightseeing Around Togetsukyo Bridge: History & Tips for Visiting Kyoto Arashiyama's Iconic Symbol

by: WESTPLAN

-

Osaka's Central Public Hall: Inside the Incredible Iconic Tourist Attraction

-

Fine Japanese Dining in Kyoto! Top 3 Japanese Restaurants in Kiyamachi and Pontocho Geisha Districts

-

Highlights of Umeda Sky Building: Get the Perfect Views of Osaka!

-

15 Attractions & Things To Do In Arashiyama For First-Time Visitors

by: WESTPLAN

- #best gourmet Osaka

- #things to do Osaka

- #what to do in kyoto

- #what to bring to japan

- #best gourmet Kyoto

- #new years in Osaka

- #what to buy in nanba

- #Visiting Osaka

- #onsen tattoo friendly arima

- #daiso

- #Visiting Kyoto

- #best japanese soft drinks

- #japanese fashion culture

- #japanese convenience store snacks

- #japanese nail trends