You surely know Tokyo’s modern skyscrapers and traditional temples, but how do regular Japanese houses look? One that a regular Japanese family lives in?

While you’re free to indulge in Japan’s bathing culture at hot springs, discover ancient arts at old theaters, or bask in colorful pop culture at Akihabara, but day to day life in traditional a Japanese home stays hidden from the vast majority of travelers.

Currently, we’re living in a time in which those old houses gradually disappear to be replaced with modern apartment buildings and the likes, especially in and around Tokyo. While the West boasts a great many buildings made from stone, Japanese houses are traditionally made out of wood, so rebuilding and renovating has to be done once every generation, as a general rule of thumb. While some Japanese houses exist that are well over 100 years old, most of them are said to have a lifespan of between 30 and 50 years. Having a traditional-style home made from wood isn’t only a lengthy process; it is also more expensive due to the skill of the carpenters required. Instead, more and more single-family houses are built from modern construction materials like steel and concrete.

When we think about traditional Japanese houses, we immediately imagine tatami, the straw mats that are so characteristic of traditional Japanese living. It’s also common knowledge that it’s common to take one’s shoes off when entering a home in Japan, and that rooms are separated by sliding doors and paper walls.

This leads to a couple of questions: do you not hear everything through those paper walls? How to sit correctly on the tatami—is that really relaxing? It seems so different from what we’re used to. Living in such a traditional house is hard to imagine. Because of that, we took our shoes off and visited such a home ourselves, asking the charming inhabitants everything you ever wanted to know about life in a traditional Japanese house!

The house we visited is about 40 years old and stands in Japan’s Hokuriku region. That’s the coastal area in the northwestern part of Honshu, the biggest of Japan’s main islands. Because of its location along the Sea of Japan, Hokuriku is known for its excellent seafood, rice, and sake breweries. Nature is lush, and there’s plenty of snow during winter. Now, let’s take a look at the unique architecture of a traditional Japanese house and how daily life is like!

1. Ima and Chanoma – The Living Room of a Japanese House

This room is called ima and is the living room of a Japanese house. This is where people relax, sip a hot cup of tea, watch some TV, and enjoy each other’s company. Chanoma is another name for such a living room. During the Showa period (from the 20s to the 80s), it was common to have a small, round table called a shabudai in this room, where people ate their meals sitting in seiza, kneeling with one’s legs folded under one’s thighs. Today, you’ll be hard-pressed to find such a table in a regular Japanese living room, as comfortable chairs and sofas are replacing the seiza position.

In winter, a lot of Japanese families relax under the “kotatsu.” That is a low table with a thick blanket fixed under the tabletop, equipped with an electrical heater. You stretch your legs under the table, snuggle with the blanket and enjoy the cozy warmth from the radiator as you watch TV, enjoy some snacks, and have a nap. During the winter months, there’s nothing better than spending a lazy day under the kotatsu.

2. Tatami – The Multifunctional Mat with a Natural Aroma

We mentioned tatami briefly, but it’s a core ingredient for every traditional Japanese house. It’s a special kind of flooring that is unique to Japan. The word tatami is said to come from the verb of tatamu, which means “to fold.” It is actually a general term for mats such as mushiro (rush mats), komo (reed mats), or goza (straw mats) – they all were folded and put away when not needed, which over time led to the word tatami. The mats you know today aren’t foldable anymore, and they aren’t put away either. Those started to take shape in the Heian period (around the 8th century).

Tatami mats are made by weaving soft rush called igusa. This plant has a peculiar and rather refreshing scent that seems strangely calming and relaxing. The woven mats also boast excellent moisture absorption, heat retention, and they’re quite soundproof. They match the characteristic of Japan’s four seasons perfectly. Elastic to a certain extent, tatami mats also make the seiza position more comfortable.

Because tatami mats are made out of all-natural material, they change over time. The color changes from subtle green to brown, and the woven grass itself gets worn. If that happens, the tatami map can be flipped, although that is something a specialized craftsman tends to help you with – it can’t be done by yourself.

Said craftsman will loosen the straw mat from the base, flip it over and sew it back on. That’ll leave you with a clean, fresh mat that looks brand-new again. Exposure to the sun is the main reason why tatami changes its color, and to Japanese people, this sight is familiar to pretty much every Japanese person and an iconic symbol of how years go by.

Tatami mats also have their own units of measurement, written with the same character put read as jo. One jo relates to one mat, with half jo being a tatami half-mat. In traditional houses, rooms are measured by how many tatami mats fit inside, such as 4.5 jo or 6 jo.

3. Oshi-ire – The Hidden Storage Space

The oshi-ire is where futons and other things are stored when not in use. A lot of Japanese people associate these kinds of hidden storage spaces with the manga/anime character Doraemon, as he sleeps in an oshi-ire. These closets are also exciting for children, as they’re perfect for playing hide-and-seek and make for excellent secret hideouts.

These storage spaces, hidden within walls, can be found all around a classic Japanese house. Another example is the tenbukuro, a little compartment usually above a closet, door, and so on. Likewise, the jibukuro can be found in the bottom part of a wall.

4. Butsudan and Kamidana – Little Altars and Shrines for Everyday Faith

A lot of Japanese homes have a little Buddhist altar called a butsudan. It enshrines Buddhist statues and mortuary tablet of one’s ancestors. The room in which such an altar is placed is called butsuma and if need be, a Buddhist priest is called to hold a memorial service there.

Additionally, you’ll find a family altar of the native Shinto belief, called a kamidana, in many houses. It usually hangs in the corner of the room, facing either south or east. It hangs above eye level and in a spot where no one walks around, but if there’s a second floor, white paper symbolizing clouds is hung from the ceiling of the kamidana. A southeast corner is generally a sunlit place, and the Shinto house altar can often be found in living rooms or the room in which the family usually gathers, so it’s a familiar sight. In the house we got to visit, it was decorated with things that weren’t related to faith, such as a child’s umbilical cord (preserved in a special box – another Japanese tradition), exam admission tickets, year-end jumbo lottery tickets, and so on. The kamidana is used to pray for a family’s health, prosperity, and happiness.

Japan is hot and humid in summer, cold in winter, has a rainy season, and is dry in autumn. Japanese houses are built with all kinds of little tricks in mind to adapt to the local climate. For ventilation, they feature a wooden veranda called engawa; tatami mats are used for heat retention; shoji paper doors and walls are excellent in absorbing moisture from the air while sliding doors quickly close or open a space for convenient temperature control. And antimicrobial, humidity-regulating keisodo – diatomaceous earth – is often used as the plaster base for interior walls. With all these, the house is perfectly equipped to handle the different climates throughout the year.

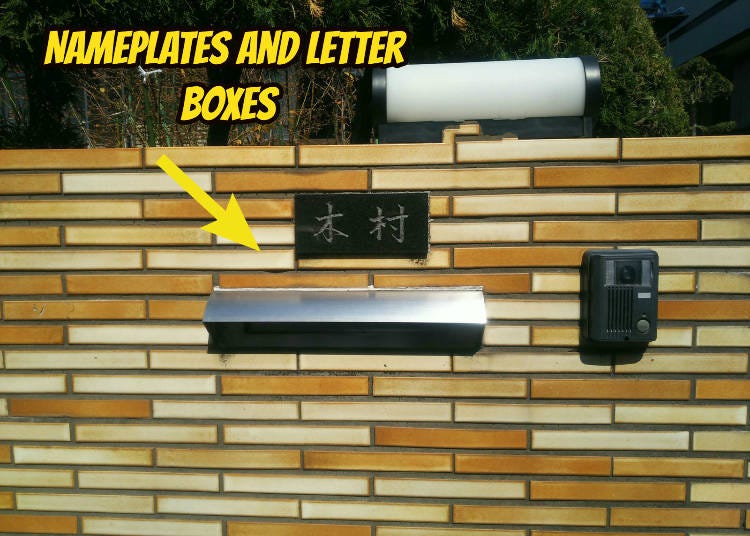

5. Nameplates and Letter Boxes – Changing With the Time

Like in many other different countries, you’ll find a nameplate and letterbox at the entrance to a Japanese house. Traditionally, nameplates are made out of stone and wood and feature the name of the resident family, spelled out in kanji characters. Recently, a lot of people opt for a nameplate out of modern material to match their house, and their name spelled with Roman characters. If someone is living with their parents, for example, it’s not uncommon to see two different names on the plate.

The letterbox is actually called shinbun-uke in Japanese, literally meaning “newspaper box.” Nonetheless, all mail goes into that one box or slot. Some families also have a milk carton right underneath for regular orders of milk and Yakult.

In recent years, the nameplate, letterbox, and milk carton have started to lose their traditional shape. The reason for that is concerns about one’s personal information, stalker incidents, and a decline in newspaper subscriptions. Today, you’ll often see only the family name written on the nameplate, and sometimes there’s no nameplate at all. Letterboxes can now be locked to prevent people from taking out mail – it’s a common trend in various countries. Traditionally, Japanese neighborhoods were very tightly knit, with everyone being acquainted, providing a structure of safety and security. Especially in larger cities, this is disappearing more and more as well.

A curious trend of the time, however, is that milk cartons are replaced by “bento boxes.” Nowadays, a lot of seniors live by themselves, and they often make use of a meal delivery service or grocery shopping service.

6. Yanegawara – Beautiful Roof Tiles with Regional Decoration

Traditional Japanese roofs feature beautiful tiles that vary in color, shape, and material, all depending on regional customs.

Here in the Hokuriku area, where the house we got to visit stands, the roof tiles are traditionally black and ceramic. The tiles are glaze fired, making them shine beautifully in the sunlight. The winter in Hokuriku is somewhat cloudy, so when the sun comes out and brings a bit of warmth, hinting at spring, the image of the sparkling roof tiles has a revitalizing effect! The gloss also makes the tiles resilient against water and thus durable. For a region with a lot of rain and snow, it’s a perfect choice.

The San’in region in the southwest of Honshu is known for its characteristic red roofs. They’re made out of high-quality clay from Shimane Prefecture’s Iwami district. Once glazed, the clay rich in iron oxide turns into vivid reddish-brown color. This glaze also strengthens the tiles against drastic temperature changes, which are characteristic for the region.

Okinawa’s “Red Ryukyu Tiles” are of a similarly vivid red. They are made from a clay-like soil called kucha – it contains bits of corals and shellfish from the bottom of the ocean. These tiles boast a high moisture absorption and breathability, making them perfect for the warm, sea-surrounded climate of Okinawa. Imagine if the roofs in Okinawa were black – they’d collect all the warmth from the sun, turning the house into an oven!

In Gifu Prefecture, you’ll find the villages of Shirakawa-go and Gokayama. They’re both designated as World Heritage Sites because of their traditional gassho-zukuri houses that feature pointy thatched roofs with a slope of about 60 degrees! It’s an area that experiences heavy snowfall, so these roofs were designed to withstand the heavy weight of a lot of snow.

7. Tataki and Agarikamachi – The Entrance to the Entrance

The entrance of a traditional Japanese house consists of three layers, so to speak. First, there’s the tataki, which is the ground floor right behind the entrance door. Nowadays, it generally is made of concrete but in the past, the pounded tataki floor consisted of earth, lime, and bittern. Another name for this pounded floor is doma.

In ancient Japan, ordinary people traveled in a kind of litter (a type of human-powered transport) called a kago, and the tataki floor in front of the entrance was used as a space to set this down. Behind that is the step called agarikamachi – from here, it’s a no-shoe zone.

The agarikamachi step is higher than the tataki floor and leads to the house’s entrance corridor. You take your shoes off at this point, leaving them on the tataki floor but close to the agarikamachi. This extra step doesn’t only prevent dirt from being carried into one’s house, it also acts as a clear separation between the outside world and the inside of a home. This is one of the most iconic characteristics of a Japanese house.

8. Shikii and Kamoi – The “Rails” of a Sliding Door

As mentioned before, sliding doors are another iconic part of a traditional Japanese home. They can be easily adjusted to separate or open a room, regulating space, light, and temperature while saving plenty of space. The “rails” that such a sliding door sits on have special names as well. The sill (bottom) is called shikii, while the lintel (top) is called kamoi.

There are a couple of curious expressions in the Japanese language surrounding these two rails. “To straddle the shikii” means “to frequently come and go,” while “the shikii is high” refers to a place that is awkward to visit. Recently, the latter phrase’s meaning has shifted a bit, and more and more people use it as “feeling self-conscious.” It’s an interesting case of old phrases adapting a modern meaning.

Stepping over the 10-cm wide rails of a sliding door carries a pleasantly refreshing feeling, as you’re entering a house’s private area.

Between the kamoi (upper rail) and the ceiling, you’ll often find a decorated part called ranma. This is where traditional craftsmanship really gets to shine in all its magnificence. It not only enhances the room with its unique decoration but also helps to keep the space ventilated. Inami City in Toyama Prefecture is particularly famous as a hot spot for these ranma decorations.

9. Fusuma – Sliding Wall Panels, Good or Bad?

Next to dedicated doors, Japanese houses also feature sliding wall panels called fusuma. They’re typically made out of a wooden frame covered with paper or cloth on both sides. These sliding screens also feature perfectly fitting rails on the floor and ceiling, and little door handles make the fusuma easy to move out of the way.

At first glance, this room is relatively small – 8 jo (tatami mats) in size. However, when a lot of people come together, for a family gathering, for example, it can easily be transformed into a proper hall! Fusuma allow you to partition your living space freely and quickly.

However, there are demerits to these sliding screens as well. You cannot lock them like a door, for example, and they’re not soundproof, meaning that you can basically hear everything said in the adjacent room. Privacy is a rare luxury in a traditional Japanese house. Modern-day Japanese families put a lot more value on privacy, so even in traditional homes, you might come across lockable doors.

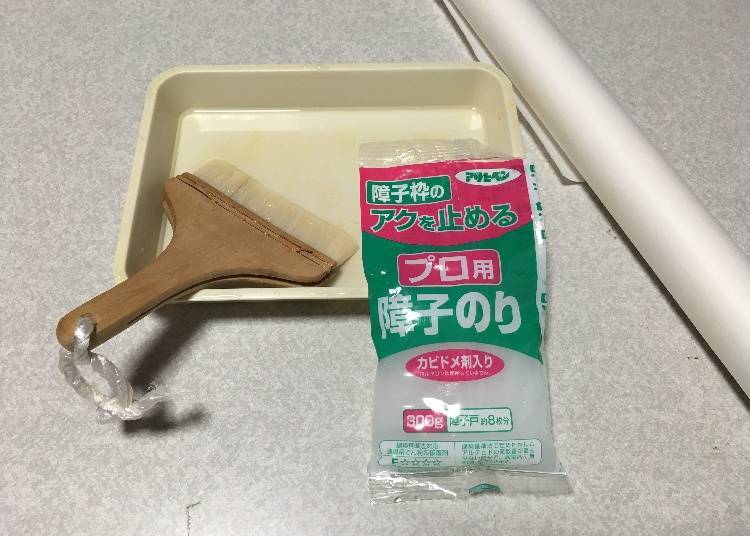

10. Shoji – Soft Lighting and Great Absorbency

Shoji is the name for the traditional paper fitted to windows and doors. It acts like a curtain, letting in just enough daylight to dip the room in a soft, warm light without being glaring. On top of that, it absorbs moisture and has great heat retention, weathering both snowfall and the rainy season excellently well.

Shoji comes in various types and designs, from the frame and paper to the layout. The one you see in the picture is called yukimi, literally translating to “snow-watching.” The bottom part can be pushed up and thus opened, allowing you to enjoy the snowy scenery outside from the comfort of your home.

The downside of shoji paper is that it gets damaged easily, making maintenance a bit of a hassle. Usually, people replace the entire paper once a year. It’s a rather time-consuming task, so instead of replacing everything, little fixes are possible. The shoji paper is then cut into a decorative shape and carefully glued over the damaged part. With this technique, all sorts of beautiful patterns can be created, truly shining when the sun falls on them. In recent years, laminated shoji paper has become more and more popular because it is a lot sturdier than the traditional option.

11. Tokonoma – A Decorative Corner

A must in every Japanese home is the tokonoma, a slightly raised alcove that is beautifully decorated, usually with a hanging scroll and an ikebana flower arrangement. Its purpose is to entertain visitors with its design and you’ll find such alcoves a lot in ryokan, traditional Japanese inns.

The seat right in front of the tokonoma, from which it is best seen, is called kamiza or seat of honor, reserved for guests of honor or the head of the family.

12. Engawa – The Open Terrace

The engawa isn’t just a terrace – it actually is a long corridor that connects the living room with the garden. Commonly, this terrace is installed on the outside and used as both corridor and entrance. When the doors are open, you can freely wander between inside and outside. Especially on warm, sunny days, the feeling of openness is blissful beyond belief. It’s a place to relax with a cup of tea and a round of shogi, Japanese chess, and much like humans, cats love wandering around the engawa or napping on the floor.

Photo credit (main image): Sakarin Sawasdinaka / Shutterstock.com

*Prices and options mentioned are subject to change.

*Unless stated otherwise, all prices include tax.

Popular Tours & Activitiess

Recommended places for you

-

Goods

Yoshida Gennojo-Roho Kyoto Buddhist Altars

Gift Shops

Nijo Castle, Kyoto Imperial Palace

-

Kambei Sannomiyahonten

Yakiniku

Kobe, Sannomiya, Kitano

-

Jukuseiniku-to Namamottsuarera Nikubaru Italian Nikutaria Sannomiya

Izakaya

Kobe, Sannomiya, Kitano

-

ISHIDAYA Hanare

Yakiniku

Kobe, Sannomiya, Kitano

-

Appealing

Rukku and Uohei

Izakaya

Sapporo / Chitose

-

Kanzenkoshitsuyakinikutabehodai Gyugyu Paradise Sannomiya

Yakiniku

Kobe, Sannomiya, Kitano

-

A Travel Game Changer! Go Hands-Free Between Tokyo and Kyoto with LUGGAGE EXPRESS by JTB and JR Tokai

by: Guest Contributor

-

Enjoy Japan's Gorgeous Winter Lights! Ride the Romancecar to Shonan no Hoseki Illumination

by: Guest Contributor

-

Black Friday 2025: These Are THE Japan Travel & Shopping Deals to Check Out

-

Ad

Walk in the Footsteps of Believers: A 4-Day Pilgrimage Across Goto Islands, Nagasaki Prefecture

by: Yohei Kato

-

2025 Autumn Colors Report: Kurobe Gorge Nearing Peak

by: Timothy Sullivan

-

Shopping, Dining & All-Day Fun! Your Complete LaLaport Guide + Exclusive Tourist Coupon

-

Best Fukubukuro Lucky Bags in Osaka 2020-2021: Japan's Crazy New Year Sales!

by: WESTPLAN

-

Exploring Tokyo Station: 11 Must-Visit Spots Around the Heart of Tokyo

-

Shopping in Shibuya: 3 Hot Souvenir Shops and Popular Products Among Tourists!

-

Top 5 Things to Do in Hokkaido's Biei and Furano Area: Shirogane Blue Pond, Lavender Fields, And More!

-

Where You Should Stay in Akihabara: 20 Best Hotels & Rentals For Visitors

-

Top 4 Go-To Spots for Tokyo Ramen

- #best sushi japan

- #what to do in odaiba

- #what to bring to japan

- #new years in tokyo

- #best ramen japan

- #what to buy in ameyoko

- #japanese nail trends

- #things to do japan

- #onsen tattoo friendly tokyo

- #daiso

- #best coffee japan

- #best japanese soft drinks

- #best yakiniku japan

- #japanese fashion culture

- #japanese convenience store snacks