Omamori, Ema, and Omikuji: Why Japanese Lucky Charms Are Amazing!

- Written by: Nao

Nowadays, Japanese temples and shrines are widely known by travelers from all over the world, so many people have an idea of what they are like.

But what about a colorful tiny drawstring-bag-looking stuff that are found for sale there? Or pentagon-ish shaped boards hanging together? Or, a paper that some visitors tie up onto a string? Have you got any ideas about what they are?

In this article, you'll find the meanings of these characteristic religious charms, when and how they came into existence, and how the Japanese today take them.

Omamori: About Japan’s traditional talismans

These colorful tiny drawstring-bag-looking items are called omamori (written with the Japanese character for "protection").

Brief history of omamori

The idea of talisman already existed in Japan 14,000 -1000 BCE. Then it became the shape of "omamori", in the Heian era, about 1000 years ago.

Back then, temples and shrines had growing power and influence. So, the people called "Oshi", who belonged to and working for temples/shrines, traveled all over Japan to acquire more believers. However, although people wanted to visit the introduced temple/shrine, in many cases, it was impossible to do as there was little choice as a means of transportation.

Therefore, omamori was born. It gave the people, who lived far away from the temple/shrine where the spirit of omamori belonged to, peace and protection.

- Hukuro mamori

- A bag type.

- Omamori ya

- An arrow type, most commonly called “Hama-ya”.

Hama means “to beat evil spirits”.

- Ofuda, Mamori fuda

- A wooden type. Also, what is inside of hukufo mamori is this ofuda.

It’s always wrapped with a white paper as it is believed that the paper protects ofuda’s power and cleanness.

- Suzu mamori

- A bell type. It is believed that the clear sound of this Japanese tiny bell scares away evil spirits, hence it protects you.

What are they?

Basically, omamori is what protects you. However, some of omamori are for a specific purpose.

- General

- To support you to live peacefully and healthily.

- Hadamamori

- To protect you both physically and mentally. You need to carry it with you all the time. In the past, people sew it onto their hada-gi (underwear), so it is called hadamamori. It is said if something as bad as hurt you happens, hadamamori will sacrifice itself to save you, so it gets cracked or broke.

- Yaku yoke

- To protect you from evil spirits, bad people/accidents/etc.

yaku = sufferings, yoke = to avoid.

- Kenko mamori

(Health) - To protect your body from disease, injury, etc.

- Shigoto mamori

(Work) - To support you to get a nice job, to succeed in your job/project, etc

- Rennai Joju

(Romance) - To support you to fulfil your love.

- En musubi (work, romance, etc.)

- To support you to connect with others. It is generally believed to help you with matchmaking. However, it can also lead you to good friends or even a nice company as 'en' in Japanese means connection, chance, and any sort of relationship.

- Kin un (Finance)

- To enhance your luck with money.

- Gakugyo mamori, Gakugyo Joju, Gokaku Kigan (Study)

- To support you to achieve the learning target or to pass the exam.

- Kotsu anzen mamori (Transportation safety)

- To protect you from accidents during transportation. The most common use of this omamori is to keep it on a vehicle you drive.

- Anzan (Easy delivery)

- To support you to deliver a baby with no trouble.

- Pet mamori

- To support your pet to live healthily.

Where can you get an omamori?

You can get them at Jimusho (at a temple)/Shamusho (at a shrine)/Juyosho, which are stands selling a variety of amulets and other items.

It is important to know that while omamori may be cute in appearance, they are religious items and not something that you ‘buy’ per se. Omamori is given by Hotoke (Buddha) or Kami (Shinto deities). Hence, the money you pass to staff is not a payment but a dedication.

How to take care of omamori?

Supposing you acquire a hukuro mamori, you should always have it on you, ideally; this can be seen as similar to a St. Christopher's medallion or similar. However, if it is a bit difficult, you can keep it at home at a place that's bright and clean. Also, if it’s possible, you should put it somewhere higher than level with your eyes.

Ofuda and Omamori ya are to keep at home. For these kinds of omamori, it is essential to put them at a bright and clean place that's higher than level with your eye.

Another important thing to remember is that ofuda is ideally placed facing a bright direction, which is to the south or the east. As for Omamori ya, keep it close to Ofuda if you possess one, and never put arrowhead up to the sky, which is believed to belong to Kami.

Omamori etiquette

Is it okay to open the bag?

No. To be precise, this bag is just a thing to protect the omamori. What omamori really has is fuda (a holy wooden piece) inside of it. And, as all fuda are blessed by hotoke/kami, it is believed that to remove it from the bag or to see it directly is disrespectful towards hotoke/kami.

Is it okay to throw it away when it gets old/dirty or when I don't need it anymore?

No. You can't just bin it. The Japanese believe that items such as this must be returned to hotoke/kami, as they filled omamori with sacred power.

There are several ways to give omamori back to hotoke/kami.

1) Simply bring it back to where you got it.

All temples/shrines have a place to gather omamori that are no longer needed. You can leave your omamori there with some osaisen (money to dedicate to hotoke/kami) to show your appreciation.

2) Send omamori back to where you got it.

If it is difficult for you to come back to Japan, it is worth checking if the temple/shrine accepts returning omamori via post.

3) Ask a temple/shrine nearby.

If there are temples/shrines near to you, you might want to ask if they are the same denomination (Buddhism) or sharing the same Kami (Shintoism). If so, they may be able to take care of your omamori on behalf of where you originally acquired it.

4) Burn it at home.

It might sound a bit barbaric. But, first of all, all the omamori brought back to the temple/shrine are to be burned. So, it might make sense to do it at home when you can't reach the temple/shrine.

To burn what you have cherished/appreciated is a Japanese religious ritual that can send the item to the top sacred place, akin to heaven in Christianity.

Thus, as a ritual, you must wrap your omamori with a pinch of salt in a clean white paper before putting omamori into a fire. (Salt is believed it can purify evil spirits.)

Is it okay to have many omamori?

Yes. You might come across someone who advises you not to have two or more omamori mostly because, considering omamori is a shared spirit by hotoke/kami, they would fight each other. But the predominant belief is that both hotoke and kami possess a merciful heart and will watch over you as long as you are respectful.

Having said that, you might want to consider whether you are getting more omamori than you can take care of properly.

What do the Japanese think of omamori?

Although it is said that most Japanese people are not overly religious, many of them still have omamori. In fact, they often obtain omamori on New Year's day when they make the first visit to a temple/shrine, or when they feel they have something out of hand so they need help from hotoke/kami.

It is also common to give omamori to people they care about, especially on the occasion of a life event. For example, parents give their children a "Gokaku Kigan" omamori when they sit for a university entrance exam.

Ema: Japanese prayer boards

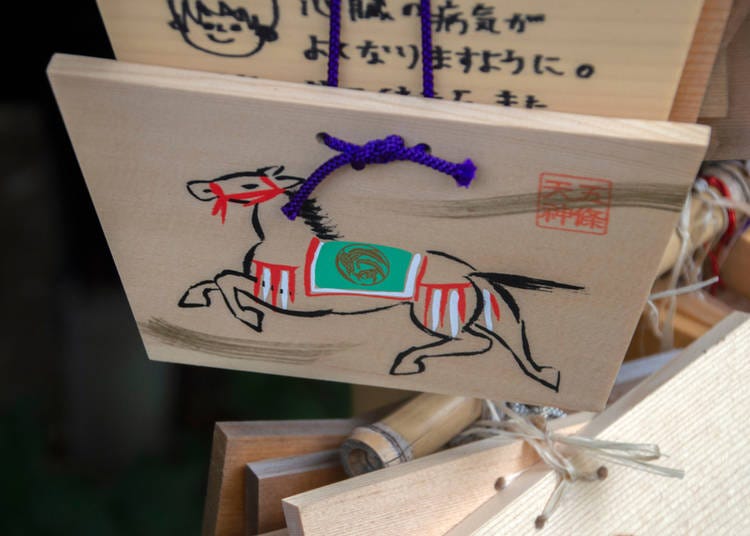

Visit most any temple or shrine and you'll see an area 'decorated' with colorful wooden boards. These are ema, Japanese wishing board.

People dedicate ema when they have a wish or when their wish has come true. The E in ema means 'picture', so it's always got a picture on it. There are not only pentagon-shaped ema but also square-shaped one or other sorts depending on the area or temples/shrines.

Brief History of Ema

In ancient times, people dedicated a live horse to kami when their wish came true. However, not all people were rich enough to prepare an actual horse, and shrines weren't able to look after all the horses that were brought in. Therefore, this custom gradually changed from a live horse to clay figures of horses and wooden horses, then to a board with a picture of a horse.

And, this is why this wishing board is called 'ema' (e=picture, ma=horse).

Nowadays, the picture on the board varies, and you can see the personality of the temple/shrine from the sorts of ema they offer.

How to write on an ema

First of all, you might wonder, does your wish have to be written in Japanese? The answer is no. If you write it from your heart, hotoke/kami will understand even though you write it in your own language.

There is not a rule when you write ema apart from to be polite and respectful. It is preferable to write your full name, address, and birthday plus year, so hotoke/kami can know whose wish it is. However, most people only use their name or initials for safety reasons.

Is it okay to bring them back to home?

Yes, on condition that you haven't written your wish on it. Treat it the same as omamori: keep somewhere clean, bright, and higher than your eye level.

Do the Japanese write ema?

Yes. Especially before a university/school entrance exam, many students will go to a shrine that has kami of studying as their symbol and write their wish on an ema. Adults also go to a temple/shrine to dedicate ema when they have something they want to achieve.

Omikuji: Japanese fortune slips

Omikuji is a type of Japanese fortune that is written on a strip of paper. These days, some temples/shrines may also have English omikuji.

The list below shows the most common kinds of luck they will tell you.

- 大吉 (Dai-kichi)

- Super lucky

- 吉 (Kichi)

- Lucky

- 中吉 (Chu-kichi)

- Lucky enough, okay

- 小吉 (Sho-kichi)

- So-so

- 半吉 (Han-kichi)

- Half-good

- 末吉 (Sue-kichi)

- It might not be your time for now, but your luck will come later (in the year)

- 凶 (Kyo)

- Bad

- 小凶 (Sho-kyo)

- Little bad

- 半凶 (Han-kyo)

- Half-bad

- 末凶 (Sue-kyo)

- Bad luck will come later (in the year)

- 大凶 (Dai-kyo)

- Very bad

Where to get (draw) an omikuji?

Before you try your luck with an omikuji, you should have something specific in mind - a hope, dream, or something else that you would like insight into.

There are typically two styles of omamori at a temple/shrine.

1) Omikuji stick version

You'll find this at the Jimusho (at a temple)/Shamusho (at a shrine)/Juyosho. If you ask staff for an omikuji, they will pass you a tubular box. Draw a stick and tell (or show) staff the number on it. Then, they give you a fortune slip with the corresponding number.

2) Omikuji paper version

You'll find a box with full of omikuji in the site of a temple/shrine, usually somewhere close to the Jimusho (at a temple)/Shamusho (at a shrine)/Juyosho. In this case, it is simple. Put a coin into Saisen-bako (a separated box attached along with the omikuji box) and draw a folded paper yourself. This will have a number on it which corresponds to a series of drawers. Then take a fortune slip from the drawer with your number on it.

What to do with omikuji?

Now that you have your omikuji, have a look at it. It's said these will provide some insight into your question.

When your omikuji tells a good fortune: You should keep it.

When your omikuji tells a bad thing: You should leave it at the temple/shrine, so that hotoke/kami can take care of your omikuji and no bad thing will happen to you. This is why people tie up their fortune slips onto a string.

When to get an omikuji?

Many people draw their fortune on New Year's day to see their fortune for the year. However, it is okay to draw an omikuji whenever you want. Just remember to say hello to hotoke/kami first before you dash straight for omikuji!

Is it okay to draw omikuji several times until I get a good one?

This is not advisable. Omikuji is a message from hotoke/kami to you. Accordingly, it can be considered disrespectful to draw omikuji again and again until you get one you like, as it equally means you are rejecting or having doubt about what they told you.

Also, even though you may have drawn a 'bad' fortune, be sure to read the whole omikuji. They always include advice from hotoke/kami as well. So, you might want to listen to their advice instead of turning a blind eye and give it another shot.

Having said that, it is okay to draw an omikuji on another day as your fortune may have changed after a while.

What do the Japanese think of omikuji?

As stated above, many Japanese people draw omikuji on New Year's Day. However, it is more of a part of an event of visiting a temple/shrine, that gives you a special atmosphere.

In general, they don't take the result too seriously especially when it tells a bad fortune. Though, at the same time, many Japanese still have religious respect for omikuji, so they bear in mind what they are told.

You might think it is a little bit challenging to try a religious thing when visiting Japan, or might be worried about being disrespectful somehow. Temples and shrines are very inviting and welcoming to people of all backgrounds. Do not hesitate to dive into a whole new culture!

Related articles

A Japanese writer who is from a city by the sea. Started writing from the age of ten. Since then, pen and notebook have always been the best friend. Loves travelling, tea, and books.

- Category

*Prices and options mentioned are subject to change.

*Unless stated otherwise, all prices include tax.

Popular Tours & Activitiess

Recommended places for you

-

Goods

Yoshida Gennojo-Roho Kyoto Buddhist Altars

Gift Shops

Nijo Castle, Kyoto Imperial Palace

-

Jukuseiniku-to Namamottsuarera Nikubaru Italian Nikutaria Sannomiya

Izakaya

Kobe, Sannomiya, Kitano

-

ISHIDAYA Hanare

Yakiniku

Kobe, Sannomiya, Kitano

-

Kanzenkoshitsuyakinikutabehodai Gyugyu Paradise Sannomiya

Yakiniku

Kobe, Sannomiya, Kitano

-

Kambei Sannomiyahonten

Yakiniku

Kobe, Sannomiya, Kitano

-

Appealing

Rukku and Uohei

Izakaya

Sapporo / Chitose

-

Ad

What Makes Japanese Yakiniku So Darn Good? Guide to Cuts, Heat, and Wagyu Know-How

-

Where to Buy a Japanese Kitchen Knife? Why Travelers Choose MUSASHI JAPAN's 14 Stores in Tokyo, Kyoto, and Nara

by: Guest Contributor

-

Ad

5 Recommended Wagyu Yakiniku Restaurants in Tokyo: Signature Dishes, Premium Beef, and Secret Sauces

-

A New Tokyo Landmark Is Coming in 2026, and It's Built for Modern Travelers

by: Guest Contributor

-

Top 3 OSHI MAPs for the Best Matcha and Sweets in Tokyo

by: Guest Contributor

-

PokéPark KANTO Is Finally Open! Tokyo's New Pokémon World Starts Before You Even Arrive (2026)

by: Guest Contributor

-

Top 5 Shinto Shrines and Power spots in Kansai for Love and Marriage

-

10 Best Hotels Near Kyoto Station: Budget-friendly, Perfect for Kyoto Sightseeing

-

Tokyo to Sendai: Riding the Shinkansen to Japan's Stunning Spots

-

Meiji Shrine (Meiji Jingu): Exploring the Sacred Sanctuary of Peace in Bustling Tokyo

-

‘No Garbage?!’ 5 Times Tourists Were Shocked by Kyoto

by: WESTPLAN

-

Numazuko Kaisho in Ueno: Good Quality, All-You-Can-Eat Seafood for Just US$12!?

- #best sushi japan

- #what to do in odaiba

- #what to bring to japan

- #new years in tokyo

- #best ramen japan

- #what to buy in ameyoko

- #japanese nail trends

- #things to do japan

- #onsen tattoo friendly tokyo

- #daiso

- #best coffee japan

- #best japanese soft drinks

- #best yakiniku japan

- #japanese fashion culture

- #japanese convenience store snacks