There is nothing quite like Japanese food. Japan is just absolutely awesome for its cuisine, and this comes side by side with one of its most famous condiments—wasabi! This amazing green stuff gives a real zing to sushi, but is also used with many other Japanese dishes.

In a lot of Japanese restaurants abroad the wasabi you may be eating is probably not 100% solely made from genuine wasabi—that is because the plant is so expensive! Even in Japan, unless you see the stem being ground before your eyes, the green condiment may very well be a mixture including horseradish, mustard and pepper.

This is partly because pure fresh wasabi loses pungency soon after grinding. In fact, the price per kilo is now upwards of $200 and increasing by up to 10% per year as demand continues to outstrip supply.

However, before you rush out to start planting some wasabi seeds it isn’t as simple as just growing it in your garden. Wasabi plants are particularly difficult to cultivate. In the wild real wasabi is found in only river valleys because it simply can’t flourish without specific conditions.

So, we went out to a wasabi farm to discover exactly what goes into making wasabi, and what it takes to be a wasabi farmer and cultivate one of the world’s most valuable crops!

Where is Wasabi Grown in Japan?

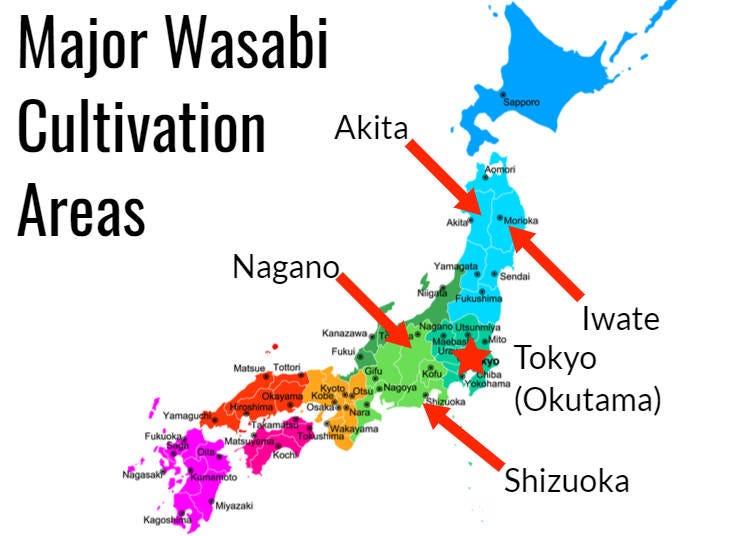

In the mountainous terrain of Japan, wasabi’s natural habitat is in river valleys. Although the plant enjoys a few hours of direct sunlight each day, depending on variety, too much isn’t agreeable, and its roots need to be able to reach into flowing groundwater. In addition, it typically won’t thrive if the air temperature is below 8 degrees or above 20 degrees. Major production areas in Japan are currently in the rural mountainsides of Shizuoka, Nagano, Akita and Iwate prefectures.

How to Grow Wasabi

Historically, however, much of Tokyo’s fresh wasabi is said to have been sourced from the mountainous region of Okutama, just outside the city.

It is in this area that the tradition of wasabi farming is continuing. Long ago, Okutama had a number of farms, many of which were said to have been made by people engaged primarily in forestry. In their spare time, they did the bulk of the backbreaking work of smashing boulders to build up terraces and irrigation ditches along mountain streams, and transporting mixtures of gravel and earth into these areas.

Though individual farms were not particularly large, each with up to only around several hundred plants, in sum they could produce a fair amount of crop. As years went by, many of the farmers gave up their trade or moved away as they aged, and the collapse of the forestry industry accelerated the exodus, while leftover Japanese cedars smother many of the old wasabi patches (wasabida).

Now a legacy of smaller growers are actively producing real wasabi for sale. Here, we met up with wasabi cultivator David Hulme, an Australian expat who’s been working to expand knowledge of wasabi farming and helping pass the tradition on to others, all while restoring old wasabida in the Okutama area.

David explains to us that quality water is really important for successfully growing wasabi plants. The roots need about a foot of good, though not too hard-packed, soil and to have access to a constant flow of water. The best water is spring water, which has nutrients and minerals, which helps the plant flourish and grow strong stems. Dissolved minerals in water that has seeped through the mountains are also what lend flavor and pungency to wasabi, and as a result many growers will locate their wasabida near favorably tasting water sources. Contrary to what many might imagine, it is the stem and not the root that is used to make wasabi paste.

In his planting areas, David positions his patches along existing mountain streams, or else uses pipes directly from a local stream to ensure that there is a constant water source flowing through. It is then important to keep checking that pipes do not become blocked and that the plants don’t get silted up.

It is also important to weed, while keeping an eye out for mildew, fungus and insect pests. At his wasabida, David checks that debris from the surrounding trees does not clog water inlets and that adequate running water is reaching each plant. In the wasabida, channels are also dug to take off any excess water during the rainy seasons and to help control the flow of water. As David goes into detail it becomes very clear how it isn’t a simple case of just watering the plants! Netting is used to keep wild animals like deer away, as they like eating wasabi leaves; I guess humans aren’t the only ones who like a bit of a taste-kick in their food!

Wasabi is also not a simple plant to grow; it won’t mature over the course of one summer. A wasabi plant can take around 18 months of careful cultivation to reach maturity. It is a fine line to tread though as if the plant gets damaged, deprived of water or smothered by silt then the stem will begin decaying and turn black. However, if a good balance can be reached between water and all the other conditions that the plants need, then after 18 months of hard work you will end up with some great wasabi plants.

A story of a Wasabi Farmer

We can’t help asking how David found himself being a wasabi plant farmer, and his story is just as interesting as the wasabi he grows! Although he had been back and forth to Japan since the early 80s it was only in the last 4 years that he really committed to living in Japan. A writer and lover of the natural environment, David is an avid outdoorsman and hiker who shifted from city life to become closer to the fresh-scented hills of rural Tokyo.

During his hikes, David was fascinated when happened upon an abandoned wasabida, and with a bit of investigating he found the owner and pitched the idea of farming wasabi. Although the owner had never worked this land, it seemed like his father had, so it had essentially been left wild for years. Today David rents this plot of land, but also works with other groups to reclaim other abandoned wasabi farms. He, along with other people he works with, believes that if the local wasabi farms were looked after properly then this area could once again thrive and become famous for its wasabi.

Reclaiming wasabi patches of old

The process of reclaiming wasabida is extremely labor-intensive—such that doing everything individually would take a great amount of time. A small group of community volunteers, local experts, and town and city officials come together to work the patch together, splitting up the work while learning techniques directly from highly experienced people. We joined in this “wasabi juku” one afternoon to see some of what is involved in the process.

Next to a gurgling stream, a two-tier terrace is placed against an old stone wall. Sunbeams filter through lines of evergreens. When we arrive early in the morning, the group is already hard at work. As the patch has already been cleared of overgrowth, today’s mission is relatively straightforward: to till the rocky soil, while washing away fine sediment with the running stream water; dig channels into which wasabi seedlings will be planted; and set up a perimeter fence to keep the wild animals away. This will involve several hours of hard work.

Wasabi farmers each take their own approach, given local conditions. Since wasabi enjoys fresh running water, the trick is to plant it in somewhat rocky soil: the rocks keep the soil in place. However, the plants will not grow in compact soil. Formerly abandoned wasabida have come to be filled in with a large amount of sediment, the top foot or so of which must first be loosened and cleared away with running water.

While expansive farms may plant wasabi into thousands of vertical plastic pipes in soil, all irrigated with massive amounts of fresh spring water, the Okutama operation is much simpler in scale. After fine sediment has been washed away, it’s time for planting.

Planting, if somewhat tedious, is fairly straightforward. A small kazusa is used to snag up the right amount of earth to keep the seedling secured, and a wasabi plant is inserted at a 45 degree angle away from the direction of flow, which helps ensure they do not get washed away over time while causing the growing stem to receive maximum water as it grows. Individual seedlings are placed about a foot apart from each other into the water-filled trenches. The process is then repeated over and over.

After planting is completed, the waiting begins. As mentioned, wasabi takes a fair amount of time to mature, which is why after one patch has been completed, work on clearing and preparing the next one begins.

Living as a non-Japanese wasabi farmer

David has proved to be quite a fascinating figure for the local people, partly because of the commitment he has made to live in Japan and learn Japanese, but also because he has demonstrated a heartfelt desire to raise wasabi. People in the Okutama region take pride in their wasabi heritage, and to have others share in this brings them great joy. As an expat, David feels very connected to the community here, and he thinks that it is interesting to be able to share a different view of things to the people around him. He can get into really fresh conversations and generate new ideas.

Amongst those ideas, one thing he is thinking to do is set up a seedling nursery. At the moment many of their seedlings come from Shizuoka and small growers have to rely on big suppliers, but these suppliers aren’t always willing to take orders for a few hundred plants here or there, given such small quantities. So, if a seedling nursery could be set up here, then it would become easier to bring back to life the local wasabi farms. If more people can get involved in growing this plant, then a more stable supply of little wasabi seedlings is essential. However, it isn’t just about getting more people working on wasabi farms; it is also about boosting the local economy and if possible attracting younger people back into the countryside to get the population growing again.

David points out that there is one local wasabi grower who produces over 50,000 plants per year, and he ensures that every single bit of his plants is used somehow, but this farmer is already in his 80s and has no one to take over. When he finally decides to retire his wasabi fields may also fall into disuse.

Using technology for regeneration

Like others in Japan who are seeking new ways to introduce Japanese culture to others abroad, David has been taking full advantage of the e-economy and technology to foster a burgeoning tourism industry in his area. With Airbnb Experiences and similar websites he sees guests from all around the world visiting this countryside area, which encourages a further sense of a young community in this amazing part of Japan. Perhaps even in the future, some of these visitors will return to Japan with hopes to start their own wasabida!

So the next time you dig into a plate of select sushi, you now have a better idea of what wasabi is all about - and can truly appreciate the amount of effort that's gone into bringing the dollop of wasabi to your plate!

- Category

*Prices and options mentioned are subject to change.

*Unless stated otherwise, all prices include tax.

Popular Tours & Activitiess

Recommended places for you

-

Jiraiya

Other Japanese Food

Sendai And Matsushima

-

Goods

Yoshida Gennojo-Roho Kyoto Buddhist Altars

Gift Shops

Nijo Castle, Kyoto Imperial Palace

-

Wasui Yaesuten

Other Japanese Food

Tokyo Station

-

MomotaroUeno

Other Japanese Food

Ueno

-

Gion Obanzai Nagatanien

Other Japanese Food

Gion, Kawaramachi, Kiyomizu-dera Temple

-

Tempura Asakusa SAKURA

Other Japanese Food

Asakusa

-

Top 3 OSHI MAPs for the Best Matcha and Sweets in Tokyo

by: Guest Contributor

-

To the Holy Land of Kawaii! Odakyu Tama Center Station Is Becoming a Dreamy Sanrio Wonderland

by: Guest Contributor

-

Farewell, Heavy Suitcases! Keisei Ueno’s New Service Makes Your Last Day in Tokyo Totally Hands-Free

by: Guest Contributor

-

PokéPark KANTO Is Finally Open! Tokyo's New Pokémon World Starts Before You Even Arrive (2026)

by: Guest Contributor

-

Ad

5 Recommended Wagyu Yakiniku Restaurants in Tokyo: Signature Dishes, Premium Beef, and Secret Sauces

-

Ad

Japan’s Land of Yokai Monsters and Spooky Stories! A Deep Journey to Mysterious San’in (Tottori & Shimane) for Seasoned Travelers

-

Dining in Nara: 9 Local Foods & Restaurants You Can't Miss

by: WESTPLAN

-

Traditional Japanese cuisine in Tokyo

-

Hokkaido Travel Guide: Everything You Need to Know Before You Go (Transportation, Food, Souvenirs & Hidden Gems)

-

Tokyo to Sendai: Riding the Shinkansen to Japan's Stunning Spots

-

Todai-ji Temple: Home to the Great Buddha of Nara - And a Nose Hole That Brings You Luck!?

by: WESTPLAN

-

Matcha: How Powdered Green Tea is Produced

- #best sushi japan

- #what to do in odaiba

- #what to bring to japan

- #new years in tokyo

- #best ramen japan

- #what to buy in ameyoko

- #japanese nail trends

- #things to do japan

- #onsen tattoo friendly tokyo

- #daiso

- #best coffee japan

- #best japanese soft drinks

- #best yakiniku japan

- #japanese fashion culture

- #japanese convenience store snacks