Unraveling the History of the Hidden Christians from Goto Islands, Nagasaki Prefecture, located in Kyushu

- Written by: Yohei Kato

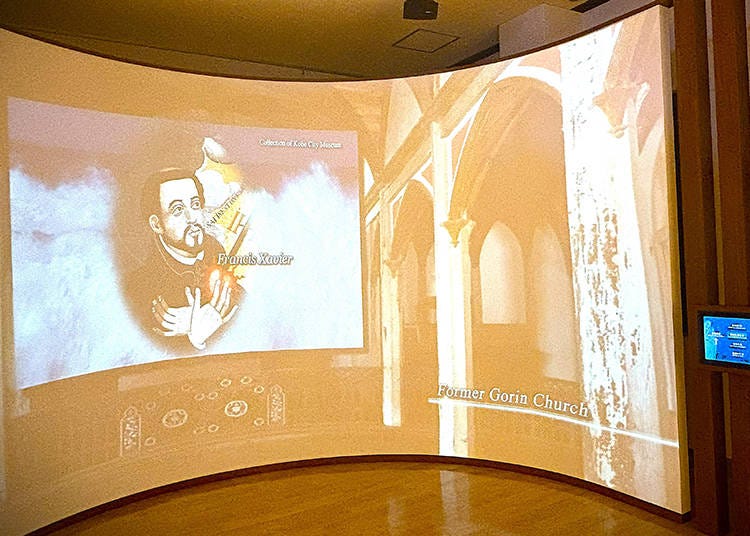

In 1549, Christianity was introduced to Japan by Francis Xavier. It spread rapidly amid the chaos of the Sengoku period (Warring States) through its ties with trade, gaining as many as 350,000 followers in only 64 years. However, that all changed when Tokugawa Ieyasu enacted a ban on Christianity.

Faced with brutal persecution and the loss of their leaders, Christians chose to keep their beliefs alive by going into hiding. The Goto Islands, remote and hard to monitor, became a place of refuge where many believers resettled. There, they built tight-knit communities and secretly passed down their faith.

In 1865, after over 250 years of silence, a miracle happened. Hidden Christians were discovered at Oura Cathedral in Nagasaki, which was proof that believers had managed to preserve their faith across Japan, including in Goto. However, this discovery led to the final and most severe persecution when the Roya no Sako Incident occurred in Goto.

In this article, we will explore the history of Christianity in Japan, from its introduction to the country, through its ban and period of persecution, to the freedom of religion, as reflected in the events that took place in Goto.

- Table of Contents

-

- The introduction of Christianity to Japan and the Nanban trade

- Why was Christianity banned? Christian persecution and ban on Christianity

- The miraculous discovery of believers and the journey to Goto

- The final persecution before the freedom of faith: the suffering and joy of the Christians of Goto

- Tracing hidden Christians’ footsteps by visiting churches in the Goto Islands

The introduction of Christianity to Japan and the Nanban trade

In the 5th century, Christianity was introduced to China through land routes but did not reach Japan at that time. After that, the challenges posed by the expansion of Islamic movements hindered European-Asian exchanges, preventing Christianity from reaching Japan for many years.

Christianity was introduced to Japan in 1549 during the Age of Discovery, when Francis Xavier, a Jesuit doing missionary work in Asia at the request of King John III of Portugal, landed in present-day Kagoshima and began spreading the faith. Why did Francis Xavier come to Japan to spread Christianity?

To answer this question, we must go back six years earlier, in 1543, when Portuguese sailors arrived in Kagoshima, bringing firearms with them. At that time, Japan was in a period of chaos known as the Sengoku period. The firearms introduced by the Portuguese were mass-produced in Japan, thus transforming the shape of war. However, Japan still lacked the necessary saltpeter for gunpowder and could only obtain lead for bullets from specific mines in the country, requiring overseas procurement.

This is where Portuguese merchants played an active part. The exchange between Portugal and Japan began with the introduction of firearms, which later led to the arrival of Christianity. Francis Xavier, who was spreading the faith in what is now present-day Malaysia, was introduced to a Japanese man by Portuguese merchants and, hearing his stories, became interested in Japan before landing in Kagoshima.

The spread of Christianity at the request of the king of Portugal progressed in Japan through collaborations between missionaries and Portuguese merchants. The daimyo (feudal lords) of Kyushu, who were trading saltpeter and lead with Portuguese merchants, converted to Christianity and used the merchants to help convert their vassals and the people of their domains.

As a result, many of their subjects converted to Christianity. Omura Sumitada, the daimyo of Hirado City in Nagasaki Prefecture, is famous for being the first daimyo in Japan to convert to Christianity in 1563 and for developing a port in a remote village. Nagasaki Port became a new refuge for Portuguese merchants and missionaries, offering them protection.

In 1566, Uku Sumisada, the daimyo ruling the Goto Islands, had his illness cured by a Portuguese missionary, which led him to help spread Christianity and support churches on the islands. It is believed that in 1606, the islands had a population of 2,300 Christians and that there were also churches.

Amid the many conflicts between daimyo during the Sengoku period, there was a need to protect Christianity, strengthen ties with merchants, and secure more advantageous conditions than other daimyo to obtain saltpeter, lead, and the latest weapons to ensure victory in battles. That is why they began trading not only with merchants from Portugal but also from Spain.

Like the Portuguese, Spanish merchants engaged in trade alongside missionary work. As a result, large acres of land, mainly in Kyushu, were granted to Portuguese and Spanish individuals under the guise of protecting Christians and merchants, as well as building churches. However, everything changed when Toyotomi Hideyoshi unified Japan in 1585. The importance of saltpeter and lead for warfare declined, and so did the emphasis on protecting Christianity.

Why was Christianity banned? Christian persecution and ban on Christianity

Tokugawa Ieyasu, who seized power after Toyotomi Hideyoshi, felt a serious sense of urgency due to the areas and people under Portuguese and Spanish control continuing to expand beyond his reach. He then set out to resolve this issue and changed Japan’s primary trading partners from Portugal and Spain, which were Catholic countries, to the Protestant Netherlands. The Dutch government promised the Tokugawa shogunate that they would separate trade from religion and refrain from missionary work.

In 1613, the Tokugawa shogunate finally imposed a ban on Christianity, placing public notices detailing its content across the country. Churches were destroyed, and more concrete actions were taken in 1614, when foreign missionaries, daimyo, and their vassals who refused to renounce Christianity were exiled from Japan. In 1616, the shogunate used the restriction of trade ports to only Nagasaki and Hirado as an opportunity to further enforce the ban on Christianity and to promote the conversion of believers. Then, in 1624, the shogunate completely prohibited the arrival of Spanish ships and ended trade with Spain.

Banning Christianity, forcing discovered believers to convert to Buddhism, and persecuting those who refused became routine practices. However, efforts to eradicate Christianity from Japan were not as extensive. Measures were limited to actions such as officials going around villages to investigate suspected Christians and the use of fumi-e, where shogunate officials would make suspected Christians step on images of Jesus Christ. Those who refused were identified as Christians and forced to convert to Buddhism. Mutual surveillance among residents and a system of informants were only implemented in certain regions.

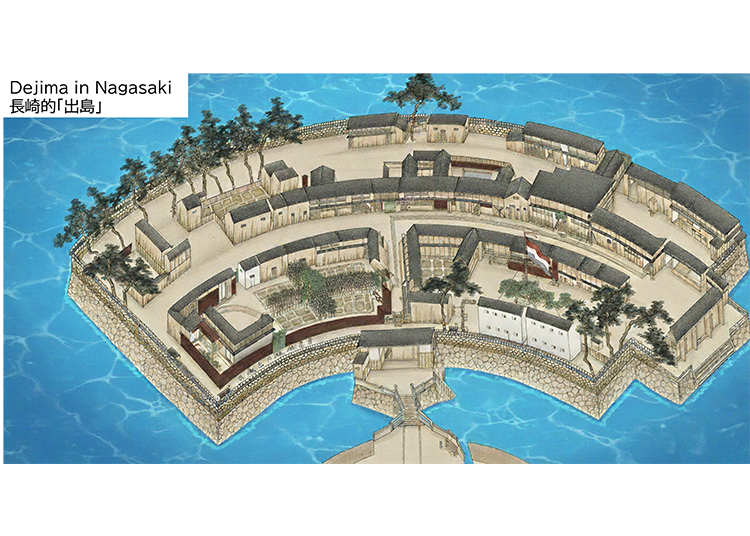

However, in 1636, Portuguese merchants were restricted to conducting trade only at Dejima in Nagasaki, and the following year, a large-scale uprising of Christians, known as the Shimabara Rebellion, erupted in southwestern Nagasaki Prefecture. Over 37,000 people put the then-abandoned Hara Castle, located at the southern tip of the Shimabara Peninsula, under siege and fought against the shogunate army for about four months.

The Tokugawa shogunate believed Portuguese merchants were behind the uprising and completely banned the arrival of Portuguese ships, restricting trade to the Netherlands. Following the Shimabara Rebellion, the shogunate implemented an exceptionally thorough and unprecedented ban on Christianity to eradicate all Christians within Japan.

To effectively identify Christians, the shogunate not only forced people to step on images of Jesus Christ and had officials patrol villages, but also established the Gonin Gumi, groups of five households that monitored one another, along with a reward system for reporting discovered Christians or missionaries.

Additionally, they introduced the Shumon Aratame, a population register that required every individual to be affiliated with a Buddhist temple. Temples issued certificates to manage their affiliated households (danka), and when a household member passed away, the temple would conduct a Buddhist funeral. While these practices posed no issue for Buddhists, they were intolerable for hidden Christians.

In 1644, seven years after the Shimabara Rebellion, Mancio Konishi, the last priest preaching in Japan, was captured and executed, leaving the country without any officially ordained Catholic priests. He was among the Christians exiled overseas for refusing to convert in 1614, the year after Christianity was banned.

After being exiled to Macau with his family, he traveled alone to Rome, joined the Society of Jesus, became a priest, and was the last priest to return to Japan in 1632 to conduct missionary work. His death left Japan without anyone qualified to teach Catholic doctrine, and for 200 years, Christianity was practiced secretly without a leader.

Christianity was introduced by Francis Xavier in 1549 and was banned only 64 years later, in 1613. As war and trade activities became intertwined, it spread rapidly in a short period, reaching a peak of around 350,000 people, over 2% of the total population. This proportion exceeds the current percentage of Christians in Japan, which is around 1%. However, following the ban on Christianity and due to the Shimabara Rebellion, strict prohibition and a system of mutual surveillance were implemented, resulting in a decline in the number of discovered Christians.

The Tokugawa shogunate and the Meiji government, which then took over, engaged with other countries under the assumption that Japan was free of Christians. Most Japanese people likely believed that Christianity had been eradicated by the early Edo period. Not only was the Tokugawa shogunate’s ban on Christianity extremely thorough, but the absence of priests to teach the religion made it difficult to understand how religious ceremonies such as baptism and mass could have persisted.

The miraculous discovery of believers and the journey to Goto

In 1858, approximately 250 years after Christianity was banned, the Tokugawa shogunate signed new trade agreements with the United States, the Netherlands, Russia, the UK, and France. Ports were opened in Yokohama, Nagasaki, Hakodate, Niigata, and Kobe. Foreigners were allowed to live under their own countries’ laws rather than Japanese law in designated areas called foreign settlements.

Oura Cathedral was completed in 1864 as a church for foreigners living in Nagasaki. It was a rare example of Western-style architecture at the time and was called “French Temple” or “Nanban Temple” by the Japanese people nearby, attracting many sightseers. Father Bernard-Thadée Petitjean, a French missionary who was in charge of the church, allowed Japanese visitors, seemingly believing in the faint possibility that Japanese Christians, who had been banned for 250 years, might still be secretly practicing their faith somewhere.

That miracle occurred on March 17, 1865, when around ten Japanese visitors revealed to Father Petitjean that they were Christians. This demonstrated that believers had preserved their faith for over 250 years despite enduring persecution and a social system designed to eradicate Christianity since 1613, all without any missionaries or clergy, who had completely disappeared from the country by 1644.

In history and population studies, generations are often defined as spanning 25 years, based on the average age at which people have children. If we consider a child born in 1613 as one generation, the faith would have been passed down through ten generations, reaching the 11th generation descendants. Given the constant threat of severe torture or death and the absence of anyone to teach them the religion, passing down the faith for ten generations can only be described as a miracle. Yet, these individuals appeared before Father Petitjean, having achieved this extraordinary feat.

Nagasaki Port, where Oura Cathedral stands, was originally the domain of Omura Sumitada, who was famous as Japan’s first daimyo to convert to Christianity. The Omura clan actively made their vassals and subjects convert to Christianity, resulting in a larger number of Christians than in other regions. Omura Sumitada was himself a devoted Christian, and in 1850, he redeveloped Nagasaki Port and offered it for the use of other Christians and merchants.

However, the emergence of a place that Japanese people could not control became a problem, which led to Nagasaki being removed from the Omura clan’s jurisdiction. The Tokugawa shogunate then established the Nagasaki Magistrate's Office under its direct control, permitting trade only with the Dutch under its supervision. The surrounding areas continued to be recognized as belonging to the Omura clan, forming the Omura Domain.

Due to the domain having many Christians, a lot of believers practiced their faith secretly. In 1657, 44 years after the ban on Christianity and 20 years after the Shimabara Rebellion, a total of 608 Christians were arrested in villages near the Omura Domain’s castle, and 411 of them were executed. This incident was not carried out by the Omura Domain itself, but by the Nagasaki Magistrate’s Office, which was directly under the Tokugawa shogunate’s control.

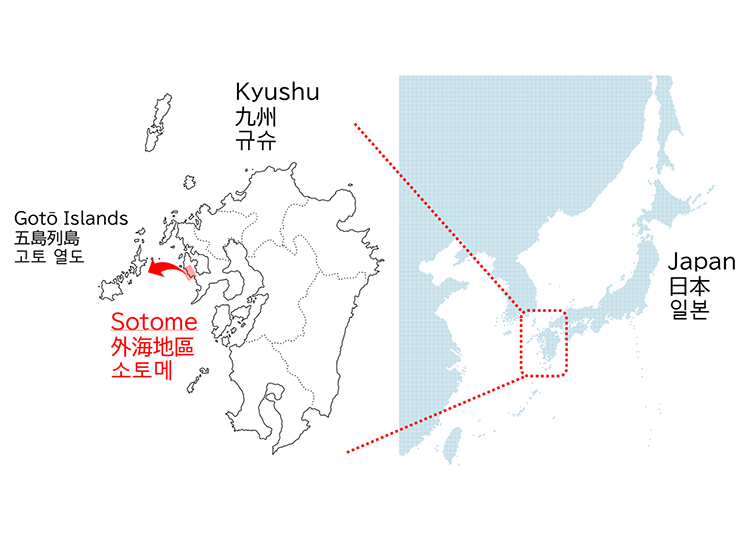

It is also said to have caused the eradication of hidden Christians around Omura Castle, the center of Omura Domain. However, there were still believers secretly practicing Christianity in areas of the domain farther from the castle, particularly in Sotome, a region overlooking the sea on the westernmost side (facing China). The region featured precipitous cliffs along the coastline and steep hills. People formed small settlements in the valleys.

Although the Sengoku period permitted Christianity, this area was difficult for missionaries and priests to visit regularly, so communities formed within each settlement to pass on their faith.

They built a system for their faith to endure even without missionaries or priests. For example, they would organize baptisms, the most important ceremony to become a Christian, and find ways to pass down the practices to the next generation. They would also preserve calendars marking Christian holidays such as Christmas and saints’ holidays.

Additionally, when the ban on Christianity was issued, they devised ways to camouflage their faith by making it appear like traditional Japanese religion. They would use common household items as tools of worship or to hide statues of Mary.

Omura Domain, which governed the area, was also somewhat aware of the presence of Christians, but the region was difficult to reach, and arresting all of them would be challenging. Meanwhile, they feared the Nagasaki Magistrate’s Office conducting another mass arrest of hidden Christians, jeopardizing the survival of the Omura Domain.

That is when the Goto Domain, which governed the Goto Islands across the sea, approached them regarding the relocation of farmers. Goto Domain at the time had a low population and could not develop new islands due to a lack of farmers.

Meanwhile, the Sotome region in the Omura Domain, which was close to the Goto Islands and easy to relocate to, was experiencing overpopulation and posed a problem for the domain due to food shortages. The region was also home to many hidden Christians, and the domain began considering sending residents to the Goto Islands.

The Sotome residents also felt anxious about the increasingly harsh control of Christians by the Omura Domain and believed that the Goto Domain would be more lenient. This led to the migration of approximately 3,000 people from the Omura Domain to the Goto Islands between 1796 and 1799, the majority of them being hidden Christians who had left their hometown to preserve their faith.

Hidden Christians from the Sotome region considered how to make a compromise by adapting to the local area and religion in order to maintain their community when deciding where to settle in the Goto Islands. This was because, although Christianity was still permitted in the Goto Domain during the Sengoku period, where the daimyo himself was a Christian, and over 2,300 Christians were living on the islands, the domain complied with the Tokugawa shogunate policy, and there were no more Christians on the islands following the ban in 1913.

The villages on Hisaka Island, one of the twelve sites making up the Hidden Christian Sites in the Nagasaki Region, recognized as a World Heritage site, were established by hidden Christians around an existing Buddhist settlement.

However, the land in this area was not suitable for farming, so they fostered relationships with the Buddhist settlement residents by assisting them with farm work and fishing, as well as renting rice paddies, while practicing their faith secretly.

There were also settlements on the same island, such as the Gorin district, where residents practiced their faith completely isolated from other settlements. The Egami Village on Naru Island, also a World Heritage site, is another settlement located on the islands in a small cove within a valley surrounded by mountains, isolated from Buddhist settlements.

They cultivated flatlands and carved houses into the slopes to form their community. The Hantomari settlement on Fukue Island is another isolated settlement.

Even today, the roads connecting these villages are so narrow that the settlements are barely visible from afar. It is easy to imagine how difficult interactions between different settlements must have been when people did not have cars, and how challenging their lives were as they hid to protect their faith. Despite many hardships, they managed to preserve their religious beliefs across generations.

The final persecution before the freedom of faith: the suffering and joy of the Christians of Goto

Good news reached these hidden Christians when, in 1864, the Oura Cathedral was completed.

Word also spread that Japanese people were now allowed to visit the church, which had previously only been accessible to foreign residents in the settlement. Representatives of the hidden Christians from Goto and other regions visited the Oura Cathedral and met with Father Petitjean to reveal their faith. They received his teachings and returned to their village to spread his words.

Christians who had been hiding gradually began to openly practice their faith and voiced their desire to hold Christian funerals instead of Buddhist ones.

The Tokugawa shogunate, which had accepted foreigners and opened the country, had somewhat turned a blind eye on Christianity, but could no longer ignore this issue. Severe persecution of Christians resumed, and in 1867, over 3,300 Christians were arrested in the Urakami district of Nagasaki and transported to various parts of the country to be tortured. As a result, 662 lives were tragically lost.

In 1868, a tragedy occurred in the villages of Hisaka Island in Goto, a World Heritage site. Two hundred people who confessed to being Christians were imprisoned in a cell measuring 19.44 m² for eight months. They were tortured and forced to renounce their faith.

The prisoners were crowded into a space about the size of a typical Japanese living room or a hotel double or twin room, with no toilet and a floor made of dirt. They would cling to the walls and take turns sitting down to rest when space allowed. This torture cost the lives of 42 individuals.

Foreign consuls, envoys, and missionaries residing in Japan strongly opposed this abuse and communicated the situation to their home countries.

In 1871, four years after the strict policing and arrests of Christians resumed, the Meiji government, which had succeeded the Tokugawa shogunate, sent the Iwakura Mission abroad to review treaties concluded with foreign nations and seek technological advancements. During their meetings with Ulysses S. Grant, hero of the American Civil War and President of the United States, Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom, King Christian IX of Denmark, and other leaders, Japan’s persecution of Christians was strongly condemned. It became clear that treaty revisions would be impossible unless this issue was addressed. Finally, in 1873, 260 years after Christianity had been banned, public notices prohibiting the religion were removed nationwide.

Their faith now recognized, Christians first established cathedrals under the guidance of foreign missionaries. Numerous churches were constructed in Nagasaki, serving as symbols and proof that Christians were permitted to preach their faith in Japan.

In 1880, the Dozaki Church was built under the guidance of French missionaries. Originally a wooden structure, it was reconstructed as an impressive brick building in 1908.

Many of these churches were funded through contributions from local Christians. For example, the Egami Church in the Egami Village on Naru Island, a World Heritage site, was built by 40 to 50 Christian households using funds raised from the proceeds of their seine fishing nets used to catch silver-stripe round herrings. The church features a small, simple wooden design with cream-colored exterior walls and light blue window frames. Since stained glass was too costly at the time, the believers used transparent glass to draw on and decorate themselves.

Tracing hidden Christians’ footsteps by visiting churches in the Goto Islands

The churches currently standing in Goto represent the Christian community’s joy in finally gaining freedom after being unable to openly practice their beliefs for 260 years, but still managing to preserve them through hiding. It is also the culmination of their pain and suffering over the years.

A church now stands at the 19.44 m² site of torture on Hisaka Island. This small, modest church, perched atop a hill overlooking the island’s bay, invites reflection on the history of the hidden Christians and will stir your emotions.

What happened there? Why did hidden Christians settle on Hisaka Island? What motivated people at the time to donate and build the many churches that now stand in Goto?

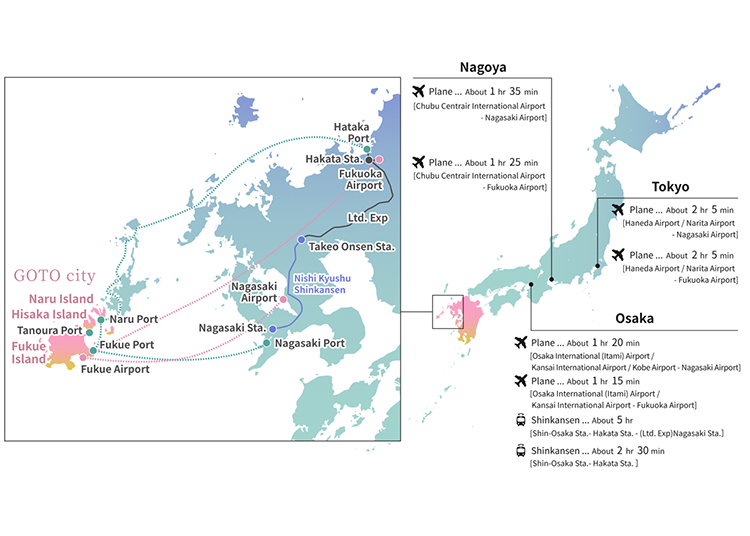

Come to Goto City in Nagasaki Prefecture for a memorable journey tracing the footsteps of believers who maintained their faith for 260 years.

- Area

- Category

*Prices and options mentioned are subject to change.

*Unless stated otherwise, all prices include tax.

Popular Tours & Activitiess

-

Top 3 OSHI MAPs for the Best Matcha and Sweets in Tokyo

by: Guest Contributor

-

Farewell, Heavy Suitcases! Keisei Ueno’s New Service Makes Your Last Day in Tokyo Totally Hands-Free

by: Guest Contributor

-

A New Tokyo Landmark Is Coming in 2026, and It's Built for Modern Travelers

by: Guest Contributor

-

Ad

5 Recommended Wagyu Yakiniku Restaurants in Tokyo: Signature Dishes, Premium Beef, and Secret Sauces

-

Ad

The Whisper of a 1,300-Year-Old History: Meet the Other Face of Nara at Night

by: Shingo Teraoka

-

PokéPark KANTO Is Finally Open! Tokyo's New Pokémon World Starts Before You Even Arrive (2026)

by: Guest Contributor

-

Ikebukuro Station Area Guide: Top 15 Spots When You Escape the Station's Maze!

-

The Best of Japan: 11 Major Cities Every Traveler Should Visit

-

Spending Wonderful Time Alone in Shibuya - Free Cosmetics and a Hundred-Yen Bus!

-

Exploring Tokyo: 4 Must-Visit Spots around Tokyo Station

-

Instagram Evergreen: Japan’s Top 10 World Heritage Sites and National Treasures!

by: Lucio Maurizi

-

Easy Day Trip from Tokyo! Ultimate Sightseeing Guide for Hakone & Lake Ashinoko!

- #best ramen tokyo

- #what to buy in ameyoko

- #what to bring to japan

- #new years in tokyo

- #best izakaya shinjuku

- #things to do tokyo

- #japanese nail trends

- #what to do in odaiba

- #onsen tattoo friendly tokyo

- #daiso

- #best sushi ginza

- #japanese convenience store snacks

- #best yakiniku shibuya

- #japanese fashion culture

- #best japanese soft drinks