Japan may be a small island nation, but each of its areas boasts a unique culture and even the climate can differ quite vastly from one region to another.

Generally, however, people tend to divide Japan into two major cultural areas: Kantō in the East and Kansai in the West. Tokyo and its metropolitan area make up Kantō, the center of Japan’s politics and economics since Tokyo became the country’s capital in 1869.

Its counterpart is Kansai, centered on Kyoto, the ancient city that has been the capital from 794 to 1869. Osaka, known as a major gourmet hot spot and often called the “kitchen of Japan,” is also part of Kansai.

Of course, such a cultural divide brings its very own subtle and not-so-subtle differences in everyday life, from etiquette to language. Sometimes, you’ll see people from different corners of Japan having trouble understanding each other because of dialects! Stereotypes are another phenomenon going hand in hand with the Kantō-Kansai-divide and it’s not uncommon to hear phrases like “Yeah, that’s how people from Tokyo are” or “Oh, they’re from Kansai, that explains a lot.”

But how do tourists experience these cultural differences? They can be quite fun to explore and discover if you know what to look out for! Let’s take a closer look at the quirks and customs of Kantō and Kansai!

Main image Osaka credit: martinho Smart / Shutterstock.com

Communication Differences: Polite Kantō vs. Open-Hearted Kansai

This might be one of the most prominent stereotypes about the differences between people from Kantō and people from Kansai. A lot of people come to the metropolitan area and especially Tokyo to study or find a job, so there are relatively few Tokyoites who actually “live in the land of their ancestors,” so to speak. That’s why there’s also a certain restraint when it comes to the relationship with one’s neighbors. Everyone brings their culture and customs from their hometown, so people are careful not to venture into the unknown, basically. That’s why people from Kantō are said to keep their distance and not approach strangers actively. Everyone strives to become a proper Tokyoite by maneuvering etiquette, rules, and manners as elegantly as possible in crowded and public places.

On the other hand, there’s Kansai and its image of being open-hearted and frank. People from Kansai have no issues talking to strangers, chatting candidly, and you’ll even come across the occasional grandma who plops down next to you in the train and offers you candy and tangerines. Especially Osaka is known for this. The city is the birthplace of a majorly popular comedy show called Yoshimoto shin-kigeki that is all about slapstick and nonsense humor found in ordinary life. Osakans grew up with this kind of comedy and are said to have a special place in their heart for it, even said to apply the typical roles of “funny man” (boke) and “straight man” (tsukkomi) to their everyday conversations and interactions. They’re said to always wanting to make everyone around them laugh, not only friends and family but also people they don’t know. Laughter works like magic for bringing people closer.

While this makes Kansai seem like a warm, kind place, Kansai’s candid way can also cause some raised eyebrows, especially among people from Kantō. The topic of money is a good example for this. Around Tokyo, it’s seen as a bit of a vulgar, improper subject, while someone from Kansai will have absolutely no issue asking “How much is that?” before exclaiming: “Too expensive!” – in their own, iconic dialect, of course. The “stingy” people from Kansai are said to always look for a bargain, eager to haggle and negotiate, while the “chic and vogue” Kantō people would see that as a faux pas.

Fashion Differences: Stylish Kantō vs. Flamboyant Kansai

There’s also said to be a clear difference when it comes to fashion and styling. In Kantō, “simple yet sophisticated” is the fashion rule to go with, while Kansai loves individualistic colors and prints. That stereotype is a particularly old one. Needless to say, it’s all a matter of personal preference in the end. However, the general image of an “auntie from Osaka” seems to be all about a preference for flashy things such as leopard print and the motto of “flashy clothes that look expensive.” There’s still plenty of people who seem to hold on to that stereotype. Of course, there are a lot of “aunties from Osaka” who prefer a simpler style...but on the streets of Osaka, you’ll spot a suspicious amount of leopard print as well!

Escalator Differences: “Stand Left” in Kantō vs. “Stand Right” in Kansai

Escalator etiquette is another prominent and very visible difference between Kantō and Kansai. It’s also one of the most famous ones. Pretty much every country has its own rules on which side to stand on an escalator, letting people pass by on the other side. In Kantō, the rule says “stand on the left and walk of the right.” If you go to Kansai, however, you’ll notice that it’s the other way around! It’s said that this can be traced back to the Osaka World Expo in 1970, people in the area were encouraged to stand on the right side instead and the rule stuck. There’s no global rule, but a lot of major cities across the world tend to stand/walk on the same side as they drive.

Kantō stands on the left side...

...while Kansai stands on the right.

Taxi Differences: Colorful in Kantō, Black in Kansai

Even taxis look different in Kantō and Kansai. In and around the metropolitan area, you’ll see taxis of various colors, including yellow, orange, white, or black. That’s because different taxi companies set different colors for their cars. The four major companies in Tokyo (Daiwa Motor Transportation, Nihon Kotsu, Teito Jidōsha Kōtsū, Kokusai Motorcars) all use yellow, for example. A company called Checker Cab has orange taxis, while the Tokyo Kojin Taxi Association’s cars are white. Black is a color used by many companies offering taxis for hire or luxury taxis, but don’t let that put you off. If you hop in a car at the taxi stand, you’ll pay the standard fee, no matter the color of the vehicle. Since autumn 2017, a lot of Tokyo’s taxi companies have started to prepare for the Olympic and Paralympic Games in 2020 and now have cars called “Blue Cab.” Their indigo blue is a traditional color of Japan.

The majority of taxis in Kansai, on the other hand, are black. That might be because of the nuance of luxury associated with the color, fitting the “shuttle service” concept well. That is just a theory, however, and no one knows the real reason behind Kansai’s taxi color.

Food Differences – Dashi: Thick Bonito in Kantō, Thin Kelp in Kansai

Gourmets and fans of Japanese cuisine immediately know what’s going on by reading the headline alone. Dashi means “soup stock” and is a major part of many Japanese dishes. Noodles such as udon and soba are generally served with or in a dashi soup, and you’ll notice that this soup differs greatly in Kantō and Kansai.

In and around Tokyo, you’ll be served your noodle delicacy in a soup so thick, you can barely see what’s in it! In Kansai, however, the broth is clear and shows you everything that’s inside the bowl. That’s because Kantō-style dashi is made from bonito and enhanced with dark soy sauce, making for a rich flavor.

In Kansai, a much lighter soy sauce is added to soup stock made from kelp and bonito. It’s a fragrant soup with a deep taste. Light soy sauce has a higher concentration of salt than dark soy sauce – that’s why Kansai’s dashi looks clear but doesn’t fall behind in flavor.

Kantō-style dashi and bonito.

Kansai-style dashi and kelp.

This difference actually affects certain products, such as Nissin’s “Donbei Udon” cup noodles. If there’s an E on the lid and ingredients list on the side of the cup, the soup is “East,” meaning Kantō style. “W” stands for “West” and Kansai style.

Food Differences – Udon: “Kitsune” vs. “Tanuki”

Let’s stay on the topic of noodles. Generally, it can be said that Kantō has a soba (buckwheat noodles) culture, while Kansai is all about udon. Even woodblock prints from the Edo period show that the people of Old Edo (now Tokyo) indulged in soba noodles! Originally, buckwheat was grown where rice couldn’t be, so Kansai with its rich soil was not a production area of soba.

But that’s where the easy part ends because this regional difference can get really confusing. Udon and soba have two major toppings: kitsune, meaning fox, and tanuki, meaning raccoon dog. Kitsune refers to fried bean curd called abura-age, while tanuki refers to crumbs of fried batter. At least that is one rule for these two expressions, as they vary from region to region and can sometimes refer to the type of noodles instead of the topping! The entire combination of udon, soba, kitsune, and tanuki is surprisingly complicated!

In Kantō, people order dishes such as “kitsune udon” or “tanuki soba,” combining topping with noodles. That order would likely not be understood in Kansai, however.

Kantō-style “tanuki udon.” In Osaka, the restaurant staff would be confused and not know whether you’d want udon or soba because the expression “tanuki” refers to soba there.

Food Differences – Okonomiyaki: Kansai Serves Rice, Kantō is Shocked!

Okonomiyaki is a dish loved and enjoyed all around Japan. It literally translates to “fry whatever you like” and is basically batter that is mixed with whatever ingredients you want. In Osaka, you’ll often get your okonomiyaki served in a classic set alongside rice and soup – but that combination is exactly what shocks people from Kantō! Japanese cuisine is all about white rice and often follows the golden rule of “one soup and three side dishes,” so serving okonomiyaki AND rice means double carbohydrates. That’s an uncommon concept and one that irritates quite a few Japanese people. It could be compared to dumplings – they’re eaten by themselves as a staple food in China, but a lot of Japanese people can’t imagine eating dumplings without rice.

Next to okonomiyaki, people in Kansai love other snack-style flour dishes such as takoyaki (octopus balls), Akashi-yaki (egg balls), ika-yaki (broiled squid), negi-yaki (like okonomiyaki but with green onions), and so on. They’re often cooked at home and you’ll find a takoyaki maker in pretty much every household in Kansai. Even sauces are available in all sorts of different varieties, a phenomenon that is exclusive to Kansai.

When it comes to flour dishes, Kantō boasts its own specialty called monjayaki. All kinds of ingredients are mixed with a rather watery batter and then grilled on a special iron, eaten straight from the hot plate. Monjayaki boasts a wonderful aroma, a rich taste, and a soft texture, feeling like a snack. In Tokyo, Tsukishima is an area that’s especially famous for its abundance of monjayaki restaurants.

Food Differences – Sushi: Kantō’s “Edo Style” vs. Kansai’s “Pressed Sushi”

Next up is one of Japan’s most representative dishes: sushi! There’s an abundance of restaurants that lets you savor luxurious sushi creations in a laid-back environment all over the country, but Tokyo has its very own nigiri sushi style called Edomae, or Edo style. Edomae basically means “in front of Edo” and refers to Tokyo Bay. That’s where Edo-style sushi was created as a fast food. Because raw fish spoils quickly, people added vinegar to enhance the shelf life and make it more delicious. That’s basically how Edo-style sushi was born.

Meanwhile, Kansai developed its own unique sushi style, one that you probably haven’t seen before. It’s called oshizushi, “pressed sushi.” Vinegared rice and fish are tightly pressed into a wooden box until everything has taken on a nice, square shape. Then, you remove everything again and cut it into bite-sized pieces. This method was also born out of the need to preserve the fresh fish. Topped with colorful ingredients and an oddly satisfying square shape, this pressed sushi is a wonderful example of how beautiful Japanese cuisine can look.

Kantō vs. Kansai: Original Dishes

Next to these prominent examples of culinary differences, there’s a plethora of original dishes to be found in both Kantō and Kansai, regularly available at any convenience store or supermarket!

Oden: Different Ingredients!

Oden is one of Japan’s most-beloved winter foods. It’s a dish of all sorts of different ingredients being stewed in dashi soup stock. During the cold months, it’s available at convenience stores and supermarkets, ready to be picked up and enjoyed immediately! Naturally, a food like this boasts regional varieties and there are certain ingredients only found in either Kantō or Kansai!

Kantō original: chikuwabu (tube-shaped flour paste cake)

Kantō original: shiro hanpen (steamed ground fish with starch)

Kansai original: ushi suji (beef tendon)

Inari Sushi: Different Shapes!

Inari sushi is a popular snack in Japan that basically is sushi rice wrapped by seasoned fried bean curd pouches. In Kantō, inari sushi has a square shape and resembles a rice bag, while Kansai likes the snack as a triangle that resembles fox ears.

Kantō’s “rice bag” shape.

Kansai’s “fox ear” shape.

Bread: Different Thickness!

Here’s another interesting detail: a loaf of white bread is cut into 6 slices in Kantō but in 5 slices in Kansai. Japanese people love egg sandwiches and in Kantō, you’ll usually find them as two slices of bread with finely chopped egg and mayonnaise in the middle. People in Kansai prefer a thick slice of fried egg in their sandwich, however.

Kansai’s fried egg sandwich.

Kantō vs. Kansai: Same Meaning, Different Nuances!

Of course, Kantō and Kansai have their own dialect and slang words. The Japanese words aho and baka both mean “stupid,” but their nuance is slightly different. In Kansai, you’ll mainly hear people use aho and it carries a nuance of humor and familiarity – it’s an endearing word, in a way. Kantō, however, uses baka a lot, with its nuance being carelessness and absent-mindedness. Compared to Kansai’s aho, Kantō’s baka seems a bit softer.

Different Words for Different Things!

A fun thing about regional dialects is that they often boast completely different words for the same thing, causing people who theoretically speak the same language to not understand each other at all. Kantō and Kansai are no exception from this and boast their very own fun examples.

At colleges in Kansai, the year that a student is in is referred to with the term kaisei. This word pretty much does not exist outside of Kansai and is only used for college students. For kids in elementary school, junior high, and high school, the general Japanese word of nensei is used. No one really knows why Kansai’s college students get such a special treatment, but one theory states that the prestigious Kyoto University first started the practice and it spread to other colleges in the area.

The picture on the left shows oshiruko, a traditional Japanese dessert. On the right, you also see oshiruko - but it’s from Kantō. If you now go to Kansai, the dessert on the left is also called oshiruko, but the version on the right is called zenzai.

The difference between Kansai’s two versions is that oshiruko is made with strained bean paste while zenzai uses coarse bean paste. Kansai is known for its many long-established shops that specialize in traditional Japanese sweets, so the distinction between strained and coarse bean paste is of major importance. Not making this distinction and simply giving both dishes the same name – like Kantō does – is seen as rather outrageous.

What and Where is Kansai?

Now that you know about some of Kantō and Kansai’s main differences, there’s just one more question that needs to be answered: where’s the border between the two? For this, we go back to Nissin’s instant udon from the beginning – the one with the different soups. The place where the E for “East/Kantō” on the lid of the noodles turns into a W for “West/Kansai” is Mie Prefecture.

On a more serious note, the town of Sekigahara in Gifu Prefecture is often quoted as the border between east and west. Here, Japan’s first shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu won the decisive Battle of Sekigahara and united the warring nation in 1600.

Tokyo, Osaka, and Kyoto are all amazing cities that have a lot of sightseeing spots, culture, and history to offer, so a lot of people will visit all of them on their trip to Japan. Whether you’ve been there already or are about to plan your next vacation, make sure to keep an eye out for the fun differences between Kantō and Kansai – sometimes subtle, sometimes obvious!

*Prices and options mentioned are subject to change.

*Unless stated otherwise, all prices include tax.

Limited time offer: 10% discount coupons available now!

Recommended places for you

-

Myoshin-ji Temple

Temples

Arashiyama, Uzumasa

-

Goods

Yoshida Gennojo-Roho Kyoto Buddhist Altars

Gift Shops

Nijo Castle, Kyoto Imperial Palace

-

Kamesushi Sohonten

Sushi

Umeda, Osaka Station, Kitashinchi

-

Appealing

Rukku and Uohei

Izakaya

Sapporo / Chitose

-

Jukuseiniku-to Namamottsuarera Nikubaru Italian Nikutaria Sannomiya

Izakaya

Kobe, Sannomiya, Kitano

-

Menu

ISHIDAYA Hanare

Yakiniku

Kobe, Sannomiya, Kitano

-

Step Into the Story: Inside Immersive Fort Tokyo

-

Where to Eat in Yokohama: 10 Must-Try Restaurants for Yakiniku, Izakayas, Unique Dining & More

-

15 Must-Try Restaurants in Ikebukuro: From Aged Yakiniku to All-You-Can-Eat Sushi, Plus Adorable Animal Cafés

-

Discover Osaka Station City: A Journey Through Its Most Fascinating Spots

-

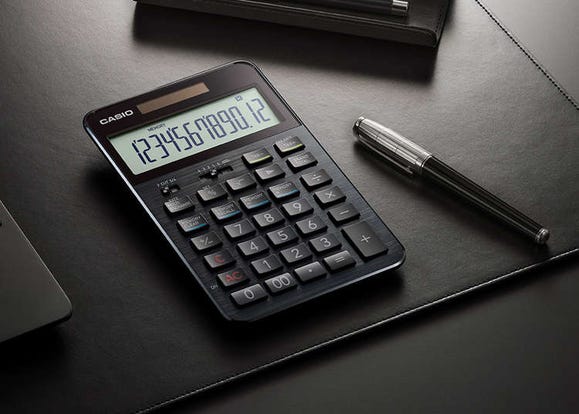

The CASIO S100: How CASIO's Masterpiece Calculator Redefines Business Elegance With Japan-Made Reliability

-

Professional Photos Even Beginners Can Shoot! 10 Tips for Taking Stunning Cherry Blossom Photos

-

Inside 'Nazuki' - Tsukiji's Chic Seafood Restaurant With Amazing Digital Entertainment

-

Bowing in Japan: Japanese Etiquette Tips (Video)

-

Inside Kobe Tower: Fun Things to Do at the Symbol of Kobe

-

6 Fun Things to Do at Tokyo's World-Famous Tsukiji Outer Market!

-

Summer Fun in Hokkaido (2024 Guide): Spectacular Landscapes, Dazzling Nights, Festivals & Essential Tips

-

Fine Japanese Dining in Kyoto! Top 3 Japanese Restaurants in Kiyamachi and Pontocho Geisha Districts

- #best sushi japan

- #what to do in odaiba

- #what to bring to japan

- #new years in tokyo

- #best ramen japan

- #what to buy in ameyoko

- #japanese nail trends

- #things to do japan

- #onsen tattoo friendly tokyo

- #daiso

- #best coffee japan

- #best japanese soft drinks

- #best yakiniku japan

- #japanese fashion culture

- #japanese convenience store snacks